We need to talk about class in improv

After a nice cup of tea, the favourite British pastime must be arbitrarily dividing ourselves up into distinct classes based on generational wealth. British improv is not immune.

In February 2025, the Guardian’s compelling series on working-class representation in the UK arts industry set out a dire picture: ‘Working class creatives don’t stand a chance’.

British improv is worse. End of article? No, sorry. I can’t speak on intersectional aspects of this (Others have so well from their own experience). However, from any angle, improv has serious social mobility issues. There is a vast over-representation of privately-educated, upper-class, performers in leading positions in UK improv, theatre and comedy generally (all worsened by Covid). We have ignored and/or failed to address it for years.

The performing arts are a hard place to feel welcome if you’re outside a narrow privileged clique. Only 7% of the UK population were privately schooled, but they represent 60% of performing arts workers. SIXTY PER CENT. You might say ‘but the arts are really left-wing and liberal. Other industries are worse’. Wrong:

Law (21% private)

Architecture (10%)

Medicine (21-50%) .

Politics? Nope, 23% of MPs are privately educated. Of 25 Cabinet members, only one was.

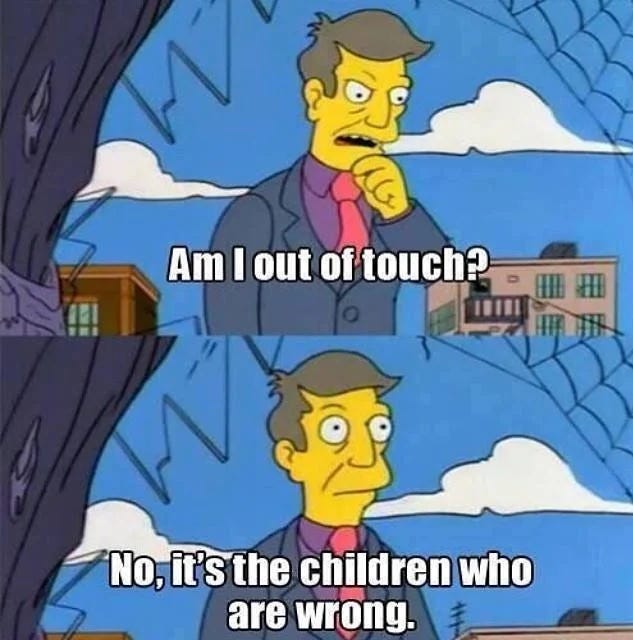

They look like bastions of inclusivity versus the arts. What excuse does improv have, other than not caring enough to fix it?

The impossibility of an arts career

I grew-up lower middle-class (NRS/ONS social grade C1, sociology nerds). I didn’t want for anything, nor did we live in luxury. I grew-up in a terrace in a diverse, deprived Northern mill-town. We had a football team once. At school (state comp), many kids had tougher backgrounds, more were wealthier. Someone’s Dad had TVs in his Range Rover headrests like Pimp My Ride.

I loved comedy growing up, mainly working-class comedians like Morecambe & Wise, John Candy, Bury local Victoria Wood was a glimmer of ‘you could do this too’. Even then they all felt like throwbacks. I also liked stuff by the higher-ups (Blackadder, Monty Python), not that you could avoid it. TV shows like Are You Being Served and Allo Allo felt like something Thatcher would like, and somehow I knew Tories didn’t share my interests.

Theatre is not something the vast majority get to see or do. I don’t recall seeing a play until adulthood, outside a school panto trip. I genuinely thought you had to wear a suit to the theatre.

At Uni in Sheffield (US-readers, all the glamour of Pittsburgh with better music), the idea someone could be privately-educated yet not at Oxbridge seemed bizarre. “If you’re so clever, how did you end up here?”.

I had no lectures in my last term (I know, lucky), so I had time to find student societies, and eventually improv. We hustled for shows in the Union bar and other pubs, organised a charity comedy festival and convinced the Alumni fund to send us to Edinburgh Fringe for 2 weeks. We had an amazing time, but had to stay 3 to a bed and feed on £2.50 sarnies from Baguette Express. The rank privilege at the Fringe was already so visibly off the charts in 2008, let alone now.

After graduating, I got a day job, before the broken economic gravity led me to London, where the streets are paved with tenants’ tears. With absolute respect to the many thriving improv scenes in other parts of the UK, London’s confluence of creative industries and investment means it unavoidably hosts the largest concentration of improv schools, venues and performers. I don’t like it either, but here we are.

Devouring as much improv as I could for a decade, a few alienating things repeatedly came up.

You can afford to do improv or act IN LONDON without a dayjob?

I luckily moved to London with a job line-up in 2012. It was a short contract, but enough for some security without parental backing. Fully planning to move back after 9 months, a bunch of extensions made that 11 years.

I made improv friends who simply didn’t need a ‘day-job’ to make ends meet. They had the best education money can buy, and remained bankrolled by asset-owning families. Many owned flats (or HOUSES!) in a famously overheated property market by their late-20s. Some are landlords.

Being frank, any money they make from improv is largely for ice cream. Improv is not lucrative - but we’re compounding the problem if the few paid teaching and performing jobs are hovered up by already privately wealthy improvisers. They might still work hard and be good at what they do. But, that’s much easier with the security to be bad and earn nothing from it, in one of the world’s most expensive cities, until that point.

By 2023, I felt confident enough to leave that job and focus on creative work. I then chowed down savings RAPIDLY and the financial precarity contributed to a catastrophic mental breakdown. In total, that’s 13 years of a 9-to-5 combined with a 5-to-9, to get partially competent in improv. Good luck sleeping, eating or anything else resembling self-care.

They know these warm ups already?

You get used to confusion if you aren’t from the dominant social clique. Some improvisers went to schools with THREE professional standard theatres. I’d done 100s of shows in the corners of bars, above pubs, tents etc, but I still didn’t perform in anything you’d call a theatre until 2013. I was 27.

As a high-school governor in a deprived London neighbourhood, I’ve sat in school board meetings where a normalised strategy is not offering music, drama or art as a subject at all, because the school isn’t judged against it, they can’t find a qualified teacher, or enough students simply aren’t interested to make it financially viable. If they aren’t doing this stuff as children, they’re not going to be queuing up as adults for your Level 5 Advanced Harold class.

Even if they somehow find it, improv workshop groups can be pretty isolating. So many times I’ve seen a privileged few derail that already know their silly warm up games from theatre school, or prep-school production of The Mikado, derail a class by cutting straight to breaking rules, before they’ve done it properly or explained them to anyone else. An apt reflection of class in the UK. Failing upwards. Zip-Zap-Feck Off.

More tea vicar? Their improv scenes are very safe

I have to use this word: posh. Posh improvisers play safe, navigating scenes like Victorian parlour games. Without adversity or any outsider perspective, word-play and overtly sexual content are go-tos.

Using pop-culture is also an easy relatable substitute for lived experience. Except the cultural shorthand references for upper class improvisers are things like Narnia, Beatrix Potter or nuances of Oxbridge college rivalries. I’ve tried, but it’s hard to care about Jemima Puddleduck flagging-down the Flying Scotsman as it charges through the Chilterns for tea and cake… Was I close?

Reared on a rigid class-scaffold: British improvisers tend to play scenes with a limited emotional range between “jolly-good sport” and “I’ve never been so insulted”. Improvisers have little chance of widening the audience by leaning on bizarre comedies of manners 90% of people can’t relate to.

They love regional accents as shortcuts for comedy characters

Anyone who has visited Didsbury or Tower Hamlets knows the North-South divide is a crude definition of class. But it’s still useful. Important things happen outside the M25: 50 million people live there.

I’m SO tired of watching improvisers from extraordinarily privileged backgrounds put on regional accents as a shorthand for an interesting ‘character’. Great that you’ve honed a passable Northern accent, but what is the joke exactly? That we have strong ‘U’ sounds, drop our Ts, make you feel a bit scared on a night out, or write the best music? Talking like a Yorkshire steeplejack doesn’t equal comedy.

If you’re in the top 1%, the sphere of characters authentically available to you is tiny. I’ve lost count of scenes I’ve watched set in audition rooms or generic white-collar offices (great, you temped in one for a few weeks).

At one London’s improv theatre, from a pool of 150+ performers, there were *seven* Northerners. This generously counts Stoke as Northern (lads, it’s the Midlands). They had to create their own team to get stage time. There’s no shortage of Northerners in London, they just don’t see improv as welcoming or relevant to them. Ask yourself why? Then consider how that applies tenfold to people of colour, LGBTQIA+, disabled or any other marginalised group.

Who you know matters

Class is a mostly invisible identity, but it’s baked into our society’s power dynamics. Britain’s powerful got there through generations of networking and entrenching a monoculture. That monoculture also defines what ‘good’ is on stage and the codes for who’s included in decision-making off-stage.

Modern long-form improv was invented by white college intellectuals: we don’t have to follow their definition of good or acceptable use/abuse of power. Without purposeful steps to avoid them, echo chambers are quickly created that reinforce each other’s views and are overly resistant to challenge.

WOW. Those chips on your shoulder must be heavy. But what can anyone do about it?

Improv should be way more accessible. There’s no props or sets required. No scripts should mean fewer academic hoops to jump through. But courses are expensive and deliberately hierarchical to milk cash from students. Vague ideas of progression and promises of stardom are sold down the pyramid. 5 levels, 8 week courses, plus electives. That’s £2k+ before you’ve seen a stage.

Aspiring performers: Institutions come and go. I’ve got football boots older than every improv theatre in London. You don’t need permission. Start your own shows, build your own audiences.

Improv leaders: The same people with the social and economic capital and motivation to set-up improv theatres are unlikely to be the best equipped to sustain them. Work harder to ensure the pipeline of performers reflects the communities where they perform. Remove unconscious and affinity biases from your syllabuses, create flatter paths to stage-time. Build more inclusive environments and address the ways your monoculture leads to exclusion. You could (should) surrender some of your own many performance opportunities and powers.

You didn’t choose your background. It’s okay. Wear your privilege well. It’s great you love improv, but earn your place. Be better than you were yesterday: You’re probably not prodigiously talented, but have been indulged with luxuries of more access, time and financial security to do the hours. If you have the power to make casting and programming decisions, address your blind spots. Make room for people from outside your experience. Champion them. And by ‘eck, please stop playing working-class Northerners unless you are one.

Endnotes

Listening: a palate cleanser from the Geordie Bruce Springsteen

Performing: DNAYS are bringing The Wunderkammer to Imperial College ‘Future Cities’ Lates this Tuesday, 11th March. TED-style talks from guest academics will inspired improvised comedy. Join us

👏🏼 such a well-written piece. I recently did one re: working class creative voices, which was actually influenced by The Guardian article you reference in the first line. The older I get the more I’m conscious of it, and the more I want to push the industry to make a change.

Also having previously worked within property, 10% of architecture coming from privately educated backgrounds feels low, based on the people I met 🫨

There’s a delusion that improv is a community. It’s not. It’s a cult-like clique. Community are inclusive, clique are exclusive.

The only way to participate is if you have money and if you don’t, you are a “yes-person”, by that I mean don’t ever tell the truth or don’t ever fall out of line, if you do you’re kicked out/ excluded.

Improv is very much divided amongst class lines, more so than any of the “boxes”, because those who make it through have the means to.

The indie stages, started by people with financial means , the players you mentioned, are like a cartel, gatekeepers of who gets stage time, giving space to people who can give them stage time.